This Budget is the most generationally regressive fiscal event in 50 years

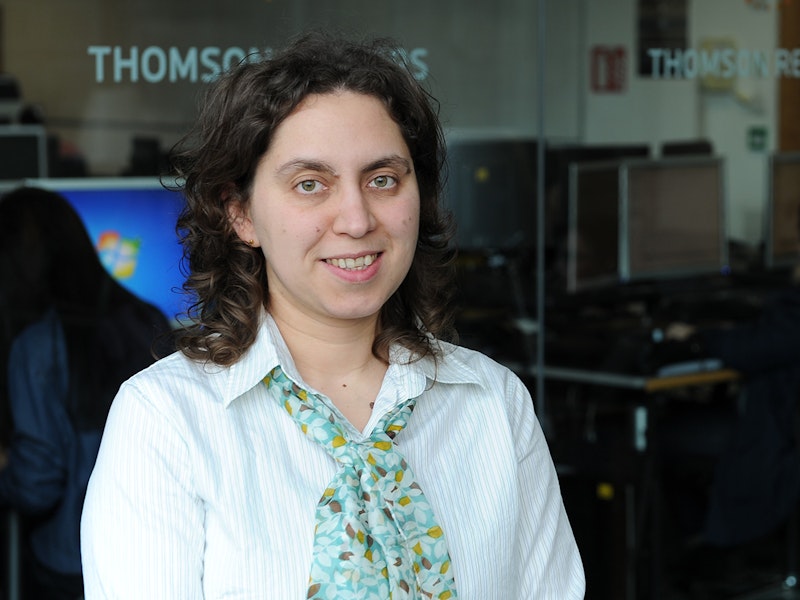

Professor Emese Lazar argues that the Chancellor has chosen the path of least political resistance, and it is at the expense of the young.

Rachel Reeves’s first budget is a 154-page document in which the word “young” appears exactly about ten times. This clearly tells you everything you need to know about the lack of commitment shown for the generation who will suffer the consequences the most. The budget provides the biggest squeeze on working-age taxpayers and the largest reduction in future growth potential. The Office for Budget Responsibility’s distributional analysis confirms that households headed by someone aged 30-39 will be £1,600 a year worse off by 2030. This is not just another tough budget. It is the most generationally regressive fiscal event in half a century.

Fiscal drag on a scale never attempted before

By extending the personal allowance and higher-rate threshold freezes to 2030–31, the Chancellor has engineered the largest unlegislated tax rise in modern British history. A median earner aged 30 today will be a higher-rate taxpayer by 2029 without ever having received a real pay rise. Once student-loan repayments (affecting the young the most), employee NICs and pension auto-enrolment are added, the marginal tax-and-contribution rate for many middle earners will exceed 55% – a level not seen since the mid-1970s for this income group.

A deliberate tax on jobs and wage growth

Raising employers’ National Insurance to 15% and slashing the employment allowance threshold to £5,000 is a direct payroll tax. The Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates that it will cost 50,000-100,000 jobs over the next five years and reduce real wages by 0.5-1%. The current high level of unemployment, of about 5%, already places unwanted pressure and burden on the young via the lack of entry-level jobs. This rate is not forecasted to improve anytime soon; it is expected to increase in 2026. Young workers, who are disproportionately in small firms and entry-level roles, will bear the brunt.

Public debt on an increasing trajectory

Public-sector net debt is now projected to peak at 97% of GDP and then – in the OBR’s central forecast – gently decline. History suggests otherwise. Every major advanced economy that has reached 90–100% debt with sub-2% trend growth has either undergone prolonged austerity or resorted to financial repression. Britain doesn’t have Japan’s domestic savings base nor the eurozone’s external surplus. The interest bill alone will absorb £120bn a year by the early 2030s – more than the entire education budget. There are not many easy alternatives to finance it – and clearly the young generation will be forced to largely contribute via higher taxation levels.

A tax burden heading to post-war peaks

Public debt needs to be serviced and doing it via increased taxation is the easy option. Tax receipts are now forecast to reach 38.3% of GDP by 2030–31; this is the highest level since 1948. This is achieved by taxing labour, consumption and investment at rates that actively discourage both.

Home ownership

Furthermore, stamp duty remains punitive for movers, disincentivising selling & buying, locking the young generation out of the housing market even further. High gilt yields, driven by the national debt trajectory, will likely keep mortgage rates between 4.5% and 5.5% for the rest of the decade. Home-ownership rates for under-35s, already at a 40-year low, will fall further.

The behavioural response of the young generation is already visible. Net emigration of 25-44-year-olds is running at post-Brexit highs. Fertility rates are drifting dangerously downwards. Additionally, labour-market participation among under-25s is falling. These are not temporary phenomena; they are rational responses to a social contract that has been unilaterally rewritten.

A courageous budget would have distributed the pain more equitably and invested in growth by introducing measures such as cutting the employers’ NI for under-30s and new hires; or by creating Singapore-style low-tax, low-regulation investment zones with full planning presumptions in favour of development; or by introducing a 50% government top-up on first time-buyer savings accounts, for example.

Instead, the Chancellor chose the path of least political resistance: tax the young and pray for growth that the budget itself makes less likely.

History will not judge this budget by the OBR’s central forecast. It will judge it by the emigration levels in 2030 and the fertility rate in 2035. Currently, both numbers are heading in the wrong direction.